(in)action movie

the pessimism of slow cinema

Breaking news: I, John D. Zhang, have been watching more films lately. (I use the term film rather than movie so as to loosely identify myself with the A24-adjacent, card-carrying indie theater member community.) Unfortunately, I haven’t very much enjoyed these supposedly elevated, upper-middle-brow works of cinema; indeed, the most memorable movie I have watched in the last two months was Madame Web, notable for how many plot points hinge not upon the titular character’s clairvoyant powers, but rather Dakota Johnson’s formidable ability to hit people with a car.

My lack of appreciation for cinema has two irritating implications: first, I may be wasting a significant chunk of time watching movies that serve no purpose, and second, the unnerving possibility that I may have bad taste. Luckily for you, I’m fundamentally incapable of believing that my takes are wrong, so what follows here is a meandering exploration of why I’m so annoyed by what I’ve been seeing. Hopefully the result is more interesting than it is incoherent.

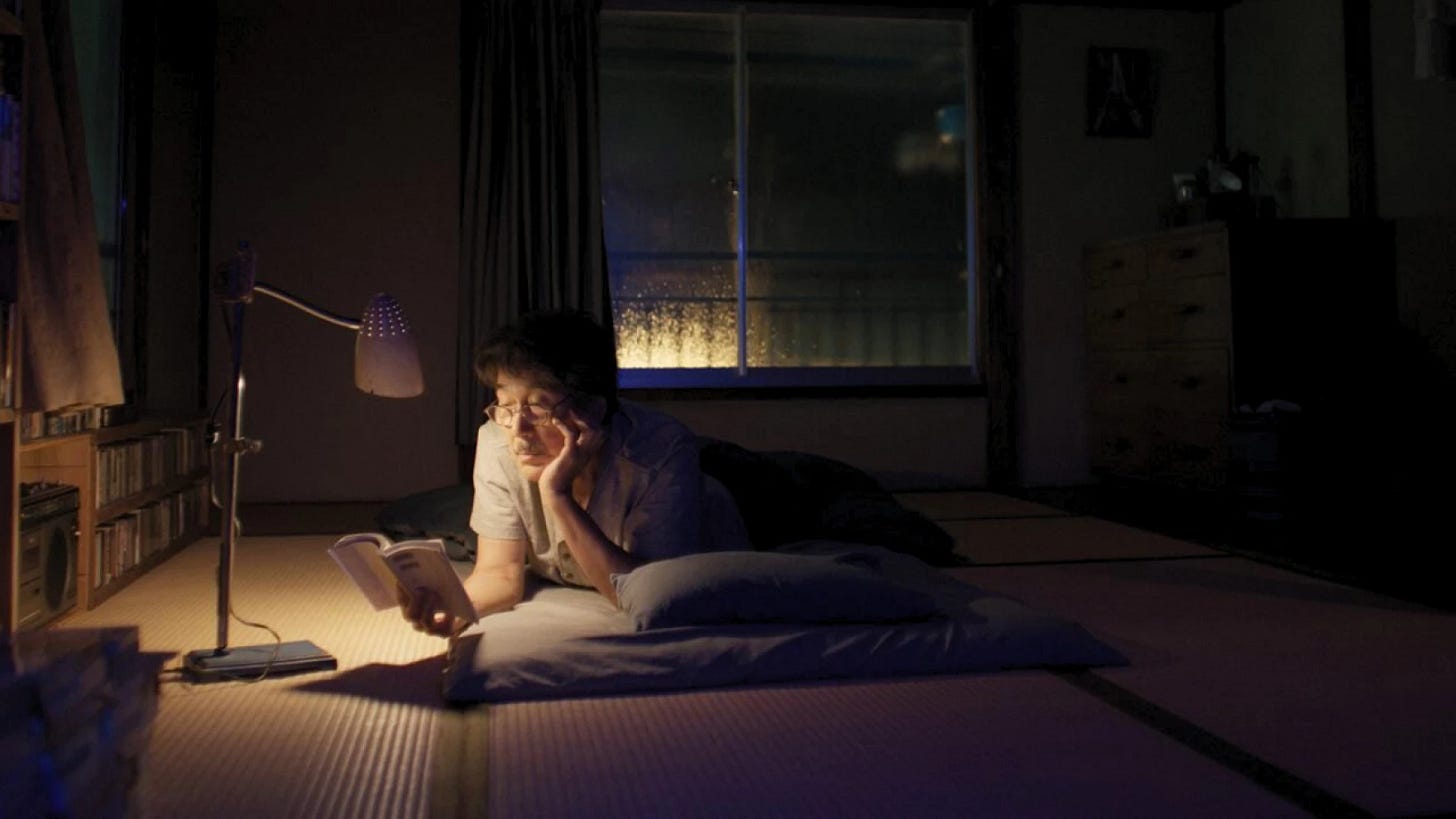

The dominant mode of contemporary cinema might generously be referred to as “contemplative” (or, less respectfully, called out as “boring.”) Take recent critical darlings Perfect Days or The Taste of Things. Compared to the nonstop dizzying motion of, say, a typical Marvel blockbuster, these films insist on longer, more deliberate shots. They take place in a relatively small number of distinct settings; the drama of The Taste of Things occurs mostly within one house (particularly the kitchen), while Perfect Days returns over and over to the same set of public toilets in Tokyo. And in both, the slow repetition of daily ritual alludes to a respect for tradition and time. Perfect Days’ main character Hirayama takes solace in his commitment to meticulously cleaning public toilets, while Eugenie and Dodin spend hours laboring over traditional French dishes in The Taste of Things to sumptuous results.

Though they don’t typify the most extreme tendencies of the style, both films exhibit characteristics of what critic Moira Weigel describes as the arthouse consensus of “slow cinema,” which is exactly what it sounds like: movies that barely move at all. Their slowness induces demands on one’s attention that are intense to the point of exhaustion. (Andy Warhol, unable to sit through his own 8-hour movie Empire, snuck out during its first screening.)

According to Weigel’s telling, the continued appeal of slow cinema is structural. In the eyes of critics, slow cinema is a much needed counterbalance to the breakneck speed of mainstream society. The last two decades have born witness to what feels undeniably like a quickening of the pace of everyday life, in which everyday people are squeezed for time and attention by increasing economic precarity and the rise of digital media. Collectively, it feels as if the pace and magnitude of sociopolitical disasters is only accelerating — 9/11, the Iraq war, the 2008 financial crisis, genocide, and, of course, COVID-19. Weigel writes of slow cinema’s appeal: “in an oppressively materialist (and violent) world, slow cinema offered respite, even transcendence.”

When does the respite offered by slow cinema become a permanent state of passivity? The appeal of slow cinema makes sense in its historical context, but surely the injunction to “slow down” begins to feel didactic after a while. In excess, contemplation might not feel so different from complacency. Comparing Still Life, a slow-cinema-style Chinese film by Jia Zhangke, and Before the Flood, a more explicitly political documentary about the same subject matter, Weigel writes of the former: “the tone is one of melancholy resignation, not protest.”

At the most basic level, narrative problems are solved when some kind of change is actuated. But in slow cinema, the aesthetics of the image is privileged over the narrative force of action: “at this pace, story slips away,” Weigel writes. These films aren’t concerned with explaining the past or attempting to reshape the future. Instead, they just are. In Perfect Days, Hirayama is visited by his estranged, wealthier sister Keiko, who expresses shock at his choice to work as a toilet cleaner and then pleads with him to visit their ailing father. This scene was perhaps the most emotionally moving of the entire film, but it was ultimately unsatisfying: Hirayama’s only reaction to Keiko is to hug her and cry. I wanted to grab Hirayama by the shoulders and shake him to his senses. Speak to her! Mend this relationship while you still have the time!

It’s not just within the bounds of his troubled familial relationships that Hirayama chooses silence over words, inaction over action. He spends nearly all of the movie barely making a sound, usually not speaking unless spoken to. This laconic mode is endemic to slow cinema: according to Weigel, scripts of slow cinema tend to be “minimal and repetitive, with little dialogue.” In The Taste of Things, the two lovers at the heart of the film rarely broach the topic of what they really mean to each other, and when they do, crucial questions are deferred. Instead, their relationship is mostly mediated through the dishes they prepare together. The food, apparently, says it all.

But in fact, it doesn’t. (That food is not literally equivalent to words is obvious to any diaspora kid who’s received a bowl of cut fruit after an argument with a parent.) Slow cinema’s allergy to language, the medium of communication at the core of what it means to be human, is what offends me most about the trend. Such sidelining of the spoken word seems to be collateral damage rather than the primary goal of slow cinema, which is to insist that a crisis of over-action, linguistic or otherwise, exists outside the walls of the theater. Ironically, that air of despondency, the unearned belief in the impossibility of action on even an interpersonal or communicative level, feels more melodramatic to me, more self-indulgently sentimental, than any earnest attempt at conventional storytelling.

Yes, perhaps the world is really falling apart this time, perhaps we have no control or agency over the systems we live under. But even in a world where so much is changing, one fundamental truth remains the same: we depend on each other to live, we exist only because others have taken care of us, we crave the security of being loved and understood. Such truths aren’t merely platitudes: they are the axioms that underpin millennia of humans doing the difficult, sustained work of existing in relation to others. To rob one’s characters of language, that fundamental connective tissue that mediates such work, is to succumb to the masculinist, Western ideal of individualism. If man is an island, he has no need for words.

Perhaps the bleakest form of this narrative malfunction can be found in Edward Yang’s Taipei Story, a 1985 movie about a troubled couple living in a Taipei marked by the growing pains of globalization. Lovers Lung and Chin can never seem to find the words to address the dysfunction in their relationship. It’s clear they are fundamentally misaligned, but they aren’t able to articulate what it is they really want, either. Lung and Chin’s slow march to mutually assured destruction was praised by international critics, going on to win a prize at the Locarno International Film Festival. It’s not surprising that film festivals are where slow cinema is most revered: according to Weigel, festivals like Locarno “served as vehicles for European soft power, exporting Western aesthetic values — including the idea of the ‘aesthetic’ itself, or the belief that art is only art when it inspires disinterested contemplation.”

But how did Taipei Story fare in its home country? According to Andrew Chan, editor at the Criterion Collection, it flopped. It was removed from theaters in Taiwan after just three days due to its poor performance at the box office and was panned for being overly self-indulgent. Here, I’m inclined to agree with the wisdom of the movie-going crowds who disliked Taipei Story more than the critics who praised it. Slowness is not inherently a virtue. Rest is not always resistance; aesthetic lethargy is often intellectually lazy.

The problems in Chin and Lung’s relationship can be seen as a metaphor for the tension between traditional and contemporary values in a modernizing Taipei. It’s exactly this conflation of the personal and political that lends an air of doom to their love. If the forces they are up against are world-historical in nature, what hope do they as two mere individuals have of ever overcoming their problems? By applying the same temporal frame to myriad different settings across time and space and yielding similar effects, slow cinema seems to imply that the personal and political always operate according to the same broken clock.

In this way, slow cinema feels like the cinephile version of #tradlife nostalgia, for a time when things changed at a less vertiginous pace than they do now. Languid and languorous, it whispers to us: the pace of change is too fast, so slow down, won’t you? But the fleetingness of such respite is made all too clear when the end credits start to roll and the lights in the theater come back on. You attempt to stand up and immediately feel a little dizzy, maybe some soreness for sitting down for so long, perhaps hunger for something more substantial than popcorn. Even as the siren song of slow cinema might have kept your mind transfixed, your body kept time. In order to respond to its demands, you have to stretch, breathe, eat. Do something, go somewhere. In both the personal and the political, the only way out is forward.

“A24-adjacent, card-carrying indie theater member community” hdhdjsj i can relateeee

I also wrote about Perfect Days and had some very different thoughts but I am so interested in this critique! Thank you for showing me this ~ film ~ in a different light. "Slow cinema’s allergy to language, the medium of communication at the core of what it means to be human"--"But even in a world where so much is changing, one fundamental truth remains the same: we depend on each other to live, we exist only because others have taken care of us, we crave the security of being loved and understood."--bangers!